ANO DO DRAGÃO

Artigo original de Ponte Ryurui

On January 23rd, 2012, we enter the Year of the Yang (陽, pinyin: yáng, lit. “sun”; male element Yang) Water Dragon, which appears in a 62 year cycle.

It is a year I have been awaiting for a long time.

Its symbolism is closely related to East Asian calligraphy, and it also gives me the opportunity to explain my pen name.

Dragons in Far Eastern mythology are benevolent creatures; bearers of wisdom, power, and positive energy. Together with a phoenix, dragon’s Yin (陰, pinyin: yīn, lit. “shadow”; female element Yin) counterpart, they are seen as an auspicious omen. Dragons and their supernatural abilities often appeared in the history of Chinese calligraphy. There were many references made to certain calligraphers or their styles, connecting them to dragons (such as Wang Xizhi (王羲之, Wáng Xīzhī, 303–361) of the Jin dynasty (晉朝, 265 – 420); more about it in this article).

Os dragões na mitologia do Extremo Oriente são criaturas benevolentes; portadores de sabedoria, poder e energia positiva. Juntamente com a fênix, contraparte Yin do dragão (陰, pinyin: yīn, lit. “sombra”; elemento feminino Yin), eles são vistos como um presságio auspicioso. Os dragões e suas habilidades sobrenaturais apareceram frequentemente na história da caligrafia chinesa. Houve muitas referências feitas a certos calígrafos ou seus estilos, conectando-os a dragões (como Wang Xizhi (王羲之, Wáng Xīzhī, 303–361) da dinastia Jin (晉朝, 265 – 420); mais sobre isso neste artigo ).

youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUaHoyochCs&w=560

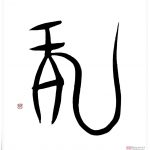

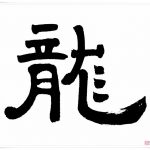

Movie 1 and Figures 1-3 Character 龍 (りゅう, ryū, i.e. “dragon”) in oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

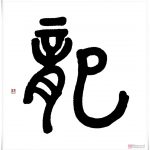

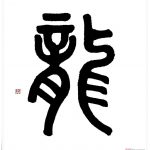

Figures 4-5 Character 龍 (りゅう, ryū, i.e. “dragon”) in small seal script (小篆, しょうてん, shōten).

Allow me to paraphrase a fragment from my book in the making titled “Marvelous Ink”, which illustrates the dragon allegory used by a Chinese calligrapher and poet of the Qing dynasty (清朝, pinyin: Qīng cháo, 1644 – 1912 C.E.), Wang Wenzhi (王文治, Wáng Wéngzhì, 1730 – 1802 C.E.):

Permitam-me parafrasear um fragmento do meu livro em produção intitulado “Tinta Maravilhosa”, que ilustra a alegoria do dragão usada por um calígrafo e poeta chinês da dinastia Qing (清朝, pinyin: Qīng cháo, 1644 – 1912 d.C.), Wang Wenzhi (王文治, Wáng Wéngzhì, 1730 – 1802 d.C.):

“Over the gateway to the Chinese city of Lin’an (临安市; pinyin: Lín’ān Shì), it is said that there was a large sign that read “Conquest of the Southeast Country”, written by master calligrapher Tu Zhuo (屠倬, pinyin: Tú Zhuō, 1781-1828). The passing of time caused a part of the second out of four characters to fade, and it was in need of a touch up. Since Tu Zhuo could not be located, his student undertook the task. Officials of the county were more than satisfied with the final result. Sometime later, Wang Wenzhi, a senior court officer, was passing the gate and stopped to read the sign. These are his famous words:

“Those four characters look like three live dragons and one dead snake (三生龍一死蛇, pinyin: sān sheng long yī sǐ shé)”.

Sobre a porta de entrada da cidade chinesa de Lin'an (临安市; pinyin: Lín'ān Shì), diz-se que havia uma grande placa que dizia “Conquista do País do Sudeste”, escrita pelo mestre calígrafo Tu Zhuo (屠倬, pinyin: Tú Zhuō, 1781-1828). O passar do tempo fez com que parte do segundo dos quatro caracteres desaparecesse e precisava de um retoque. Como Tu Zhuo não pôde ser localizado, seu aluno assumiu a tarefa. As autoridades do concelho ficaram mais do que satisfeitas com o resultado final. Algum tempo depois, Wang Wenzhi, um alto funcionário do tribunal, estava passando pelo portão e parou para ler a placa. Estas são suas famosas palavras:

“Esses quatro personagens parecem três dragões vivos e uma cobra morta (三生龍一死蛇, pinyin: sān sheng long yī sǐ shé)”.

The dead snake referred to the corrected character.

The moves of a Master calligrapher resemble those of a dragon in flight. The calligraphy is so alive and vigorous that it seems to contain a dragon’s spirit flowing in the brush strokes, as if the traces of ink were lit on the fire of motion, eluding us with its three dimensional reality, reaching our soul with its spiritual arms.

youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=874i3XRqLlQ&w=560

A cobra morta referia-se ao personagem corrigido. Os movimentos de um Mestre calígrafo lembram os de um dragão em vôo. A caligrafia é tão viva e vigorosa que parece conter o espírito de um dragão fluindo nas pinceladas, como se os traços de tinta se acendessem no fogo do movimento, iludindo-nos com sua realidade tridimensional, atingindo nossa alma com seus braços espirituais.

Movie 2 and Figures 6-8 Character 龍 (りゅう, ryū, i.e. “dragon”) in clerical script (隷書, れいしょ, reisho)

Calligraphy is the art of meditation. Devoting one’s entire life to one art wholeheartedly purifies the mind and blesses that person with a mythical aura of wisdom. The personality of the old masters I have met is defined by their calligraphy. It is so simple, yet so deep, so sensible and untouchable. For me they are the reincarnations of ancient dragons. They float above everyday desires, like clouds above over-heated summer ground, close enough to maintain eye contact, yet far enough away to hear nothing but the songs of void skies. Watching them write makes me wonder whether or not they really need a brush to write at all. They have become the art itself.

youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N7ib0bHwVIk&w=560

A caligrafia é a arte da meditação. Dedicar a vida inteira a uma arte purifica de todo o coração a mente e abençoa a pessoa com uma aura mítica de sabedoria. A personalidade dos antigos mestres que conheci é definida pela sua caligrafia. É tão simples, mas tão profundo, tão sensato e intocável. Para mim são as reencarnações de dragões antigos. Eles flutuam acima dos desejos cotidianos, como nuvens sobre o solo superaquecido do verão, perto o suficiente para manter contato visual, mas longe o suficiente para não ouvir nada além das canções dos céus vazios. Observá-los escrever me faz pensar se eles realmente precisam ou não de um pincel para escrever. Eles se tornaram a própria arte.

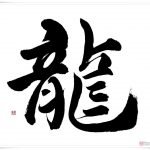

Movie 3 and Figures 9-12 Character 龍 (りゅう, ryū, i.e. “dragon”) in cursive script (草書, そうしょ, sōsho).

So many people ask me why I chose the pen name 龍涙 (りゅうるい, ryūrui, i.e. “Tears of Dragon”). I believe that the following passage from my book (quoted above) should explain it very well.

“The dragon is the guardian of my soul, watcher of my ancient spirit. Its endless wisdom opens up many new paths in my life and lifts them up like a magical torch, leading me to a state of internal peace and spiritual tranquility, a place in time where surroundings and reality are not relevant but cease to exist, allowing me to submerge myself in ever-lasting legend.”

youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yMXPogyKtPU&w=560

Muitas pessoas me perguntam por que escolhi o pseudônimo 龍涙 (りゅうるい, ryūrui, ou seja, “Lágrimas de Dragão”). Acredito que a seguinte passagem do meu livro (citada acima) deveria explicar isso muito bem.

“O dragão é o guardião da minha alma, observador do meu antigo espírito. A sua infinita sabedoria abre muitos novos caminhos na minha vida e os eleva como uma tocha mágica, levando-me a um estado de paz interna e tranquilidade espiritual, um lugar no tempo onde o ambiente e a realidade não são relevantes, mas deixam de existir, permitindo-me para submergir em lendas eternas.”

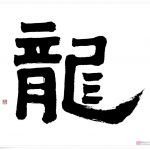

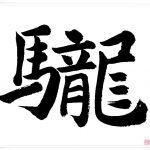

Movie 4 and Figures 13-15 Character 龍 (りゅう, ryū, i.e. “dragon”) in standard script (楷書, かいしょ, kaisho).

“Tears symbolise passion and a profound understanding of Sho (書, しょ, lit. “to write”; here: East Asian calligraphy), aesthetics through senses, curiosity, and the essence of the primordial values of the Universe. The shiny ink is the very tears being poured like waves of energy, raw feelings from the bottom of my soul barreling on wings of detached mind like a wild dragon, pure as a child’s dream. It is an echo of sudden eruption a thousand years old, an elusive form of appreciation of what is not changeable by human will, thrown subconsciously and with sacred appreciation onto paper, in a blink of time.”

“Tears of the dragon” become ink of the soul. Ink is a Yang element of calligraphy, being soft, supple and warm, and it contrasts with the Yin element, paper. Together they bring harmony. Since the ink is a fluid, and to make it one requires water, it is strongly connected to the water element in the Chinese theory of the Five Elements (五行, pinyin: Wǔ Xíng).

These are:

Wood (木, pinyin: mù), Fire (火, pinyin: huǒ), Earth (土, pinyin: tǔ), Metal (金, pinyin: jīn), and Water (水, pinyin: shuǐ). To read more about the interactions between those elements, please see my article here.

youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDRAqvkaw8I&w=560

“As lágrimas simbolizam a paixão e uma profunda compreensão do Sho (書, しょ, lit. “escrever”; aqui: caligrafia do Leste Asiático), da estética através dos sentidos, da curiosidade e da essência dos valores primordiais do Universo. A tinta brilhante são as próprias lágrimas sendo derramadas como ondas de energia, sentimentos crus do fundo da minha alma voando nas asas da mente desapegada como um dragão selvagem, puro como o sonho de uma criança. É um eco de uma erupção repentina com mil anos de idade, uma forma evasiva de apreciação daquilo que não é mutável pela vontade humana, lançada subconscientemente e com apreciação sagrada no papel, num piscar de olhos.”

“Lágrimas de dragão” tornam-se tinta da alma. A tinta é um elemento Yang da caligrafia, sendo macia, flexível e quente, e contrasta com o elemento Yin, o papel. Juntos eles trazem harmonia. Como a tinta é um fluido e para produzi-la é necessária água, ela está fortemente ligada ao elemento água na teoria chinesa dos Cinco Elementos (五行, pinyin: Wǔ Xíng).

São eles:

Madeira (木, pinyin: mù), Fogo (火, pinyin: huǒ), Terra (土, pinyin: tǔ), Metal (金, pinyin: jīn) e Água (水, pinyin: shuǐ). Para ler mais sobre as interações entre esses elementos, consulte meu artigo aqui.

Movie 5 and Figures 16-20 Character 龍 (りゅう, ryū, i.e. “dragon”) in semi-cursive script (行書, ぎょうしょ, gyōsho).

For calligraphers, this year is very special. The Water Dragon’s spirit lives in the ink. Its wisdom is its deep colour, its spirit is the flowing energy (行気, pinyin: xín qì, lit. “moving spirit”), its power and momentum is the kasure (掠れ,かすれ, i.e. “streaks of white paper piercing through the ink strokes”), and its immortality is the fact that calligraphy, be it on paper or in the hearts of people, lives on, remaining as mythical as the dragons, revealing its most cherished secrets only to those who live by it. Some people do not believe in the existence of dragons. I have heard that dragons mourn the existence of such people.

On the day of the 31st of December, I was writing calligraphy of the character for dragon (龍, pinyin: lóng) in five major calligraphy scripts. I treated oracle bone script (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) separately, although, in a broad sense, it is a part of the Seal Script family. Each of the scripts has its separate video (Movie 1 combines both oracle bone script and small seal script examples). I hope that you will enjoy watching them as much as I enjoyed writing the character.

Para os calígrafos, este ano é muito especial. O espírito do Dragão de Água vive na tinta. Sua sabedoria é sua cor profunda, seu espírito é a energia fluida (行気, pinyin: xín qì, lit. “espírito em movimento”), seu poder e impulso é o kasure (掠れ,かすれ, ou seja, “faixas de papel branco perfurando os traços de tinta”), e a sua imortalidade reside no facto de a caligrafia, seja no papel ou no coração das pessoas, continuar viva, permanecendo tão mítica como os dragões, revelando os seus segredos mais queridos apenas a quem dela vive. Algumas pessoas não acreditam na existência de dragões. Ouvi dizer que os dragões lamentam a existência de tais pessoas.

No dia 31 de dezembro, eu estava escrevendo a caligrafia do caractere do dragão (龍, pinyin: lóng) em cinco escritas principais de caligrafia. Tratei da escrita “oracle bone” (ossos oraculares?) (甲骨文, こうこつぶん, kōkotsubun) separadamente, embora, em um sentido amplo, ela faça parte da família “Seal Script” (escrita do selo). Cada um dos scripts tem seu vídeo separado (o Filme 1 combina exemplos de script de “osso de oráculo” e script de pequeno selo). Espero que você goste de assisti-los tanto quanto eu gostei de escrever o caracter.

Fonte

LINKS INTERESSANTES

OBRAS DE DIONISIO GONZÁLEZ QUE UNE ARQUITETURA CONTEMPORÂNEA, FOTOGRAFIA E FAVELA

Photographs Reimagine Brazil’s Shantytowns